Decoding Nature's Codec: How Singing Mice Rewire Our Future

- Whistle Mechanism: Singing mice produce sound via a whistle-like mechanism, not vocal cords, allowing both long-range songs and short-range ultrasonic squeaks from a single process. - Brain Circuit: The same brain region controls both complex songs and simple squeaks in singing mice, suggesting evolutionary repurposing of existing neural structures. - Potential Applications: Research could disrupt healthcare (e.g., aphasia, autism) and AI (e.g., speech recognition) by providing new models for vocal communication.

Experts conclude that the singing mouse's vocal and neural mechanisms offer a blueprint for understanding complex communication systems, with implications for AI, human health, and evolutionary biology.

Decoding Nature's Codec: How Singing Mice Rewire Our Future

COLD SPRING HARBOR, NY – December 01, 2025 – In the cloud forests of Costa Rica, a small rodent sings. It’s not the familiar, high-pitched squeak of a common house mouse, but a complex, audible song used to communicate across distance. This is Scotinomys teguina, Alston's singing mouse, and it has become the unlikely protagonist in a story that stretches from evolutionary biology to the future of artificial intelligence and human health. New research from the esteemed Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL) is decoding how these creatures perform their vocal feats, and the findings suggest that nature has already solved some of the most complex engineering problems in communication.

For investors and executives accustomed to tracking disruption in software and silicon, the key takeaway is this: the next major breakthrough might not come from a clean room, but from a cloud forest. The study, led by CSHL Assistant Professor Arkarup Banerjee and published in Current Biology, provides a foundational look at the biological hardware and software behind complex vocalization, offering a new blueprint for innovation.

Evolution's Efficiency: The 'Whistle Mechanism'

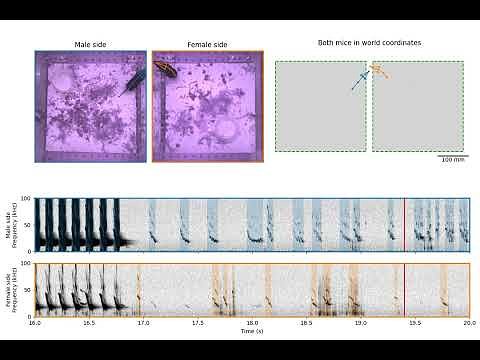

At the heart of the discovery is a fundamental question: how do these mice sing? While most mammals, including humans, produce sound by vibrating their vocal cords, the CSHL team suspected something different. They confirmed their hypothesis with a surprisingly simple experiment. By having the mice inhale helium—a classic “party trick” that makes voices sound higher—they observed that the pitch of both their long-distance songs and their close-range, ultrasonic squeaks went up. This was the smoking gun.

"For both USVs and songs, the pitch went up," says Banerjee. "So, we know for sure that they're produced by a whistle mechanism." This means the sounds are generated by forcing air through a narrow passage, much like a flute or a whistle, rather than by vibrating tissue. While whistle-like mechanisms are known in other animals, such as toothed whales and some rodents for specific calls, the CSHL research reveals this single mechanism is responsible for the singing mouse's entire advanced vocal repertoire. It’s a masterclass in evolutionary efficiency, creating a dual-mode communication system—long-range audible broadcasts and short-range ultrasonic whispers—from a single physical process.

This finding challenges the assumption that new, complex behaviors require entirely new biological tools. Instead, it demonstrates how evolution can repurpose and refine existing structures to create novel capabilities. It’s a principle that mirrors strategic innovation in business: breakthrough products are often born not from inventing every component from scratch, but from cleverly integrating and optimizing existing technologies in a new way.

The Brain's Shared Operating System

Perhaps the most strategically significant finding lies not in the throat, but in the brain. The researchers used advanced viral tracing techniques to map the neural circuits controlling these vocalizations. The result was another surprise: Alston's mice use the exact same brain region for producing their complex songs as they do for their simple ultrasonic squeaks. Furthermore, this is the same region that ordinary lab mice, who cannot sing, use for their own basic vocalizations.

This discovery is a critical piece in the puzzle of how complex behaviors like social communication evolve. It suggests that the evolutionary leap from a simple squeak to an elaborate song did not require the development of an entirely new neural control center. Instead, nature appears to have modified and expanded upon a pre-existing, conserved brain circuit. "We have found what is common," Banerjee explains. "So now the hunt is on for what's different."

This insight has profound implications. It points to a modular, scalable architecture in the brain, where foundational systems can be adapted to support more sophisticated functions. For technologists, this mirrors the concept of a software platform, where a core operating system can run a wide variety of applications, from the simple to the complex. Understanding this biological platform could provide a new paradigm for designing more adaptable and efficient artificial neural networks. Dr. Banerjee's prior work, which identified a specific motor cortex region responsible for the conversational turn-taking seen in singing mice duets, further reinforces that the brain leverages distinct but interconnected modules for vocal production and coordination.

The Translational Leap: New Markets in Health and AI

While the research is foundational, its potential applications represent a significant disruption vector for both the healthcare and technology sectors. The CSHL team explicitly points to the implications for human communication disorders, such as stroke-induced aphasia and the profound social communication challenges associated with autism.

Human speech is vastly more complex and largely learned, a key distinction from the innate songs of mice. However, by providing a working model of a mammalian brain circuit dedicated to complex vocal control, this research offers a new way to investigate what happens when these circuits are damaged or develop atypically. For conditions like aphasia, where patients struggle to produce language after a stroke, therapies often focus on reactivating and rerouting neural pathways. The singing mouse model could help researchers test strategies for strengthening these foundational motor circuits for vocalization.

Similarly, in autism spectrum disorders, where altered brain connectivity can impede social communication, understanding the evolutionary basis of vocal circuits provides a new lens through which to study the disorder's neurobiological roots. It shifts the focus toward the fundamental mechanics of vocal interaction, which could pave the way for novel diagnostic tools or therapeutic strategies.

The most direct market disruption, however, may be in the field of artificial intelligence. The press release notes the findings could "help engineers make AI better at recognizing specific words and noises." This is more than just a passing comment. Natural language processing and speech recognition have made incredible strides, but they still struggle with the nuance, context, and efficiency of biological systems. The singing mouse's brain is, in effect, a highly optimized codec—compressing and decompressing complex communicative intent through a shared neural pathway. By reverse-engineering this process, researchers could unlock new principles for designing AI that not only understands words but also the intent and structure behind them, leading to more natural and robust human-computer interaction.

Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory's deep dive into the vocal world of a tiny mouse is a powerful reminder that transformative innovation often emerges from the relentless pursuit of fundamental knowledge. The song of Scotinomys teguina is more than just a biological curiosity; it’s a signal, broadcast from the deep past of evolution, that could very well shape the strategic landscape of technology and medicine for years to come.